Alissa Marotta

Exploration 3- Magazine Article

Cloning Noah’s Ark by Robert Lanza, Betsy Dresser, and Phillip Damiani

Scientific American Magazine

The World Conservation Union-IUCN Red Data Book each year lists all of the endangered species that are now off limits to be traded. The Convention of International Trade in Endangered Species then bans the selling of any of the species products to be sold. One of the most recent endangered species is the gaur. A gaur is an ox-like animal found mostly, but now, rare in India, Indochina, and Southeast Asia. The Red Data Book claims that to date, there are approximately 36,000 gaurs remaining. Because of this fact, actions are now being taken to conserve these animals, as well as others in the future, by cloning them. As of right now, an Iowan cow is scheduled to give birth to a baby gaur, whose name will be Noah.

Scientists insist that in order to conserve and preserve our endangered species, cloning is necessary. Cloning offers a way to preserve animals that are low in species number, to protect animals reluctant to reproduce in zoos, and to bring back animals that may already be extinct. It also shows proof that an animal can give birth to an exact copy of a different species simply through in vitro fertilization. Genetic diversity would also then become stable once again. The problem, however, is how to acquire these cells from two different species to produce the clone of one.

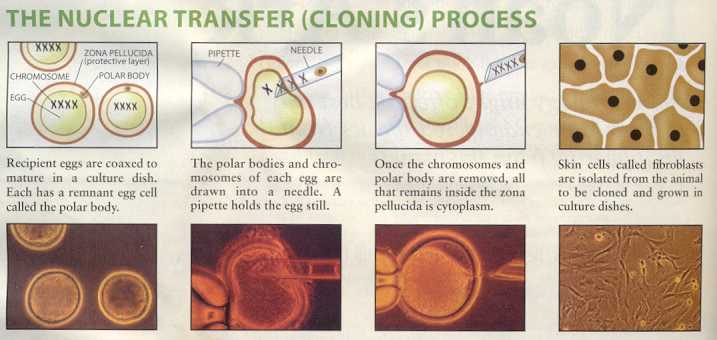

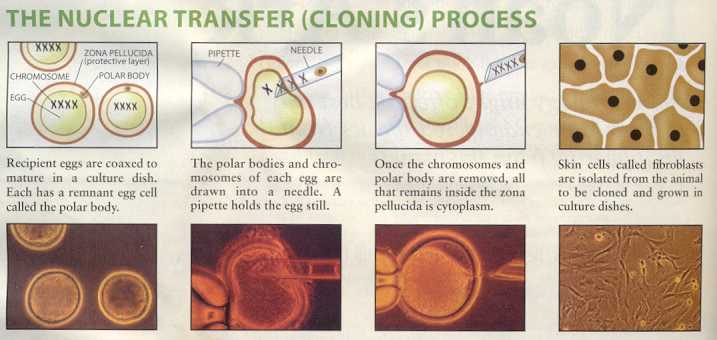

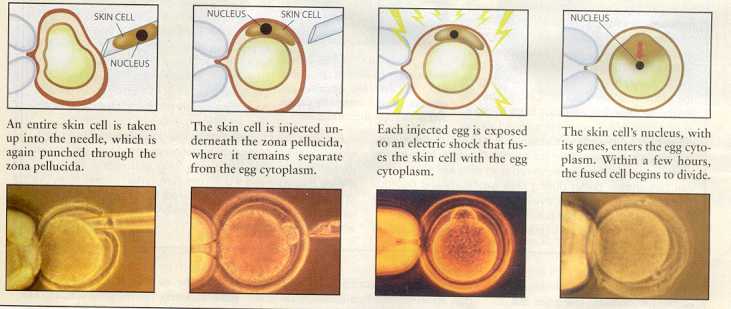

The process of cloning seems somewhat simple. The egg’s nucleus, where most of the genetic material is found, is taken through a needle. The needle is injected into the protective layer of skin. There, it draws the material from the nucleus leaving only cytoplasm behind. Another needle is then used to inject another cell in the egg’s outer layer. An electric shock is used to join the new cell to the egg. In just a matter of days, the embryo divides into a collection of cells that will be used to impregnate the chosen surrogate mother. The female, in just a few months, will give birth to the clone.

The process, known as nuclear transfusion, though promising, is also not always 100% effective. As in the case of Noah, out of 32 cows that received the injections, only eight became pregnant. Fetuses were taken from two of the cows for analysis, four suffered early miscarriages, and the seventh, suffered a very unexpected late miscarriage, thus leaving only the one Iowan cow. Obviously the process is not as easy as it would seem to be.

In conclusion, though cloning would seem to be the simplest and most effect way to preserve our endangered species, clearly it is far from being 100% effective. Researches continue to work to find what it would take to reach that point, though. The authors of this article are strongly in favor of using cloning as means of conservation and disagree strongly with those who claim that cloning would limit already declining numbers. They also disagree with the theory that cloning may outdo the preservation of habitats. They believe that many countries are too poor to maintain such efforts anyway. The writers assess that the growing human populations would make it impossible to save habitat in which the animals need, and by cloning, the populations in captivity would not have to be saved. They say that action must be taken now, and it will definitely be interesting to see what happens in the near future, especially once Noah is born.